Nietzsche’s Morals and Aestheticism

- Roxanne Noor

- Oct 29, 2023

- 2 min read

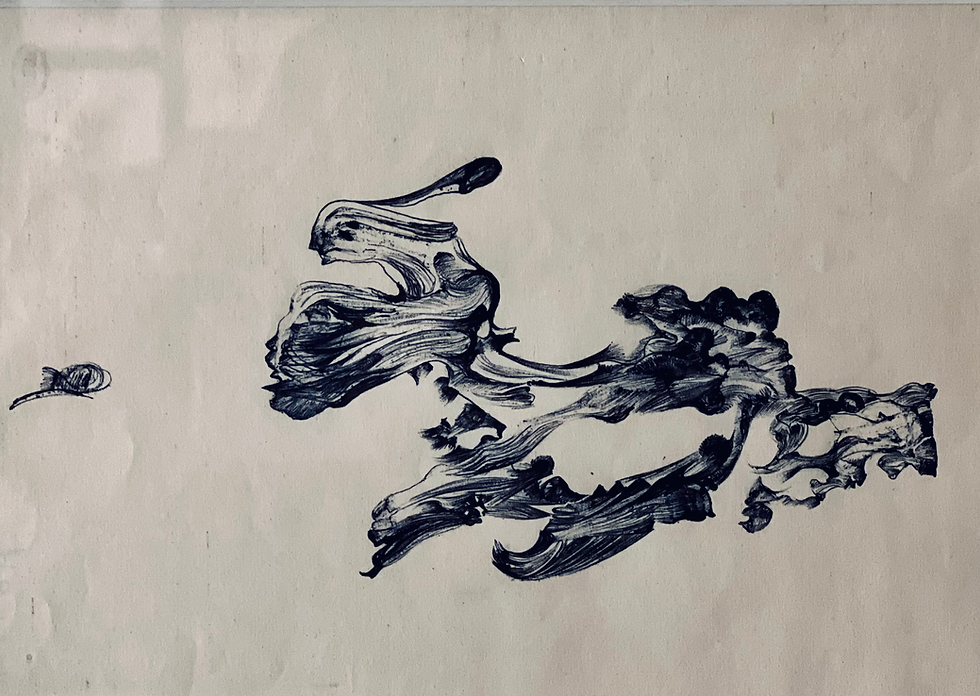

Nietzsche was one of the primary philosophers to contemplate the symbiotic relationship between aestheticism and morality. People’s perception of aesthetics often emerges from societal definitions of value, which, in turn, becomes intricately linked to our sense of morality, as we extend benevolence to that which we deem valuable.

Extending this line of thought, we can understand how the atrocity of slavery was largely rooted in the perceived lack of aesthetic value assigned to black skin compared to its white counterpart. This perceived aesthetic disparity erected a mental barrier which halted egalitarianism and the preservation of black lives.

In "Thus Spoke Zarathustra," Nietzsche proposed the concept of a "transvaluation of values," advocating for the reevaluation and reinterpretation of traditional moral values. This process of reevaluation is a constant in history as it was with slavery, but also with the treatment of women, the relationship with the environment, and consumption of animals. All beings and systems are in a constant renegotiation of moral code.

But, aestheticism affecting morality is still present. What we see as ugly we treat in an ugly manner. The less aesthetic a person or thing is, the less regard and morality it is treated with. Beauty becomes synonymous for worth.

People kill spiders happily, but not butterflies because they have an aesthetic beauty that we can comprehend and agree upon, therefore protect. We do the same with youth. We ignore the elderly and declare them useless. We do the same with women, the most stereotypically beautiful are at the top of the social pyramid and the bigger or older women are not handled with the same care. The imperative is to treat all sentient beings with dignity and witness the way in which our sense of justice fluctuates based on aesthetics.

Nietzsche's emphasis on the "will to power" states that the individual's creative, artistic nature underscores his views on morality. He urges individuals to embrace their instincts and exercise creative will, and reject the imposition of external moral codes.

A friend of mine once told me that symmetry of the face and thinness of the body didn’t evoke emotion or any appeal to him; they were low-hanging fruits. True beauty, for him, lay in the strangeness of facial features—a long nose, an unconventional jaw line, or a wide, toothy smile. His aestheticism stemmed from an untrained, innate perspective, driven by his will to power and an instinct to appreciate the world through his own fresh eyes.

We must unsee. A humanistic approach to life isn’t simply to view everyone as beautiful, but to cultivate a more nuanced, inclusive moral compass that recognizes the intrinsic worth of all beings. We must unsee all we’ve been told is unworthy. We must make our goodness blindly giving.

Comments